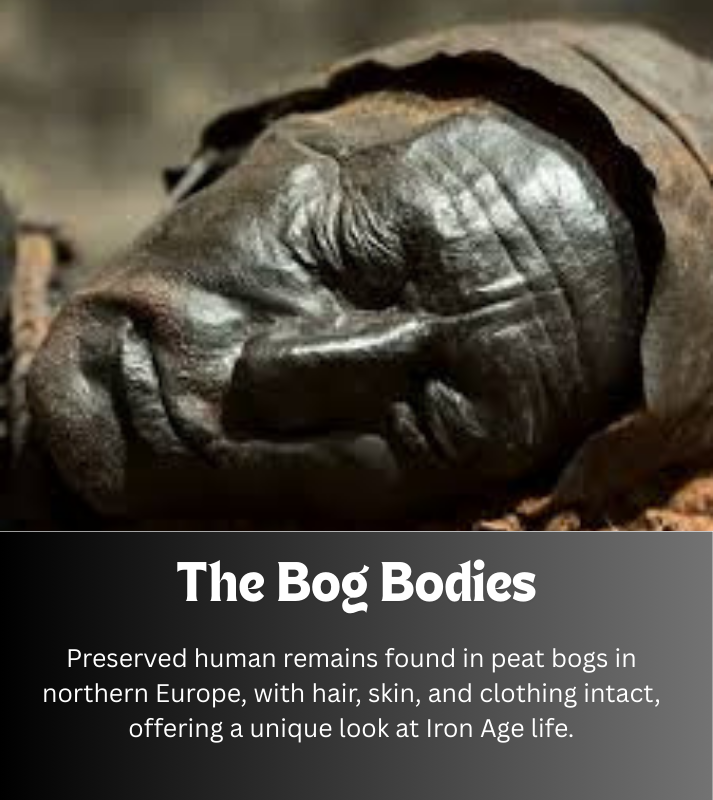

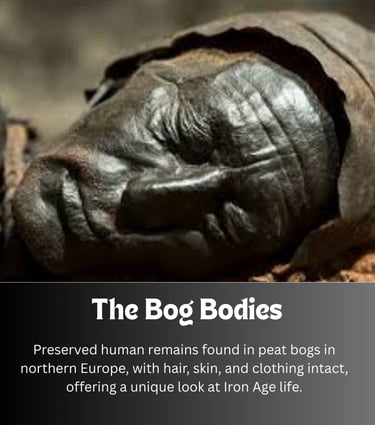

The Bog Bodies

Preserved Secrets of the Iron Age

The term "Bog Bodies" refers to hundreds of human remains, dating mostly to the Iron Age (c. 800 BCE to 400 CE), that have been found astonishingly well-preserved in the peat bogs of Northern Europe (Denmark, Germany, Netherlands, Ireland, and the UK). Unlike typical skeletal remains, the unique chemistry of the bogs has mummified the soft tissues—preserving hair, skin, internal organs, and even clothing—offering an unprecedented, detailed window into a mysterious period of human history.

The Perfect Corpse: How Bogs Preserve Life

The remarkable preservation of the bog bodies is a completely natural phenomenon, often described as a form of natural "pickling." This process requires a precise and rare combination of conditions:

High Acidity (The Tanning Agent): The water in raised peat bogs is highly acidic (with a pH similar to vinegar) due to the presence of sphagnum moss. The acid acts like a tanning agent, effectively turning the skin into a kind of leather.

Low Temperature (The Slow Down): The bogs are cold, especially in the winter and early spring when most bodies appear to have been deposited. This low temperature dramatically slows down the rate of bacterial decomposition.

No Oxygen (The Anti-Rot): Bogs are waterlogged, stagnant environments, which makes them anaerobic (lacking oxygen). This environment suffocates the aerobic bacteria that typically cause soft tissue to decay.

Europe’s Natural Mummies

The unfortunate irony of this perfect preservation is that while the skin, hair, and organs are preserved, the acidic water often dissolves the calcium phosphate in bone, meaning many bog bodies have wonderfully preserved skin but little structural skeleton.

Portraits of the Iron Age:

The bog bodies are invaluable not just as curiosities, but as direct evidence of Iron Age life and culture—details that cannot be found in traditional archaeological sites.

1. Hair, Skin, and Grooming

The preserved faces and bodies reveal details of appearance and social status:

Hair Styles: The Clonycavan Man (Ireland) used a "hair gel" made of plant oils and pine resin, imported from as far as Spain, to style his hair into a high quiff, suggesting a high social status and a surprising level of international trade.

Grooming: The Lindow Man (UK) had a neatly trimmed beard, moustache, and manicured fingernails, indicating he was likely not accustomed to heavy manual labor and was potentially a man of high standing.

The "Red" Hair: Many bog bodies, like the Grauballe Man (Denmark), appear to have reddish or ginger hair. This is not their natural hair color, but a result of the bog's acids reacting with the hair's protein (keratin), causing a color change during the centuries of preservation.

2. Clothing and Diet

When found, the individuals are often naked, as linen or other plant-based fibers disintegrate in the bog. However, animal-based materials remain:

Wool and Leather: Bog bodies are occasionally found with clothing made of wool or leather, such as the Tollund Man's pointed skin cap and leather belt, or the elaborate woolen dresses of the Huldremose Woman.

Last Meal: Analysis of the stomach contents is often possible, revealing the individual's last meal. The Tollund Man's stomach, for example, contained a gruel of barley, flax seed, and wild weed seeds, showing a diet typical of the time, often suggesting a ceremonial meal.

A Ritual of Sacrifice?

The most persistent and chilling mystery surrounding the bog bodies is the cause of death. While accidental drowning is possible for some, most of the best-preserved bodies show clear signs of violence:

Hanging/Strangulation: The Tollund Man was found with a tightly-drawn leather noose around his neck, suggesting death by hanging.

Overkill: The Lindow Man suffered multiple traumas, including two blows to the head, a broken neck, and strangulation by an animal sinew cord, suggesting a highly ritualized or complex killing.

Decapitation: The Yde Girl (Netherlands) was strangled and stabbed, and her hair was partially shorn on one side.

Archaeologists theorize that these deaths were often acts of ritual sacrifice to fertility or earth deities, particularly given that the bogs themselves were often considered liminal, sacred spaces by Iron Age communities. The careful placement of the bodies—sometimes anchored down with sticks—suggests a desire to keep the person in the bog, perhaps to placate the gods of the mire.

Discover the extraordinary and unique stories.

Inspire

© 2025. All rights reserved.